Review Article | Open Access

Targeting NLRP3 inflammasome-driven neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease

Yanhua Wang1, Hua Li2

1Department of Pharmacy, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi'an 710032, P.R. China.

2Department of Chinese Materia Medica and Natural Medicines, School of Pharmacy, Air Force Medical University, Xi'an 710032, P.R. China.

Correspondence: Hua Li (Department of Chinese Materia Medica and Natural Medicines, School of Pharmacy, Air Force Medical University, No. 169 West Changle Road, Xi'an 710032, Shaanxi Province, P.R. China; Email: lihuasmile@aliyun.com).

Asia-Pacific Journal of Pharmacotherapy & Toxicology 2026, 6: 1-10. https://doi.org/10.32948/ajpt.2025.12.08

Received: 16 Oct 2025 | Accepted: 21 Dec 2025 | Published online: 04 Jan 2025

Key words Alzheimer's disease, NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles, neuroinflammation, Aβ accumulation, microglia, neurodegenerative diseases

Mounting evidence now suggests neuroinflammation as a key culprit behind disease onset and progression in AD [5]. Neuroinflammatory responses are usually accompanied by the accumulation of Aβ and abnormal phosphorylation of tau-associated proteins in cerebral tissue of individuals with AD. Formation of Aβ plaques triggers microglia and astrocytes, which then emit a broad range of inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines and chemokines, capable of triggering and sustaining neuroinflammatory responses [6]. As neuroinflammation increases, damaged neurons are removed or repair processes are disrupted, and neuronal cell death and brain tissue atrophy increase. Neuroinflammation is usually brought about by the activation of the immune cells that live in the brain, specifically astrocytes and microglia, which modulate cerebral immune activity through the discharge of inflammatory signaling molecules such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α [7]. Prolonged neuroinflammation not only exacerbates neurologic damage, but may also create a vicious cycle that further promotes disease progression. Specifically, the inflammatory response leads to elevated levels of oxidative damage in neurons in the brain, which promotes abnormal phosphorylation of tau proteins [8]. Aberrant phosphorylation of tau proteins forms neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), structures that not only disrupt the neuronal microtubule system, but may also directly damage neurons through other pathways [9].

A considerable amount of research suggests that regulation of neuroinflammation could represent a novel approach for AD treatment. For example, researchers have experimented with the administration of pharmaceuticals that reduce inflammation, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), to reduce neuroinflammation [10]. However, such drugs have not been effective in clinical trials, possibly because they do not effectively target specific inflammatory pathways or their anti-inflammatory effects do not play an important part in the complex pathology of AD. Some researchers have proposed that the accumulation of Aβ and its toxic effects on neurons can be attenuated by targeting and inhibiting inflammation-related signaling networks, including the NF-κB network [11, 12]. There has been a lot of interest in the NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor family pyrin structural domain content 3) inflammasome in recent years as a key component of the intrinsic immune response. NLRP3 is an inflammasome that may identify intrinsic and exogenous stimuli such as cellular injury and pathogenic infections, activate downstream caspase-1, and promote pro-inflammatory cytokine (IL-1β and IL-18) production [13]. An increasing amount of investigations have shown that NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles play a central role in neuroinflammatory responses, and their aberrant activation may be one of the important mechanisms in the progression of AD. In the neuroinflammation of AD, the NLRP3 inflammasome is regarded as an important regulator, and its activation may lead to microglia overreaction and pro-inflammatory factor release, which may exacerbate neuronal injury [14].

The aim of this work is to examine the function of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles in AD and their potential clinical implications. We will describe the basic architecture and operation of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles and discuss their mechanism of action and potential as therapeutic targets in AD, as well as current research advances. By gaining a more profound insight into the part NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles play in AD, this paper hopes to offer innovative perspectives and methodologies for the prompt identification and treatment of AD.

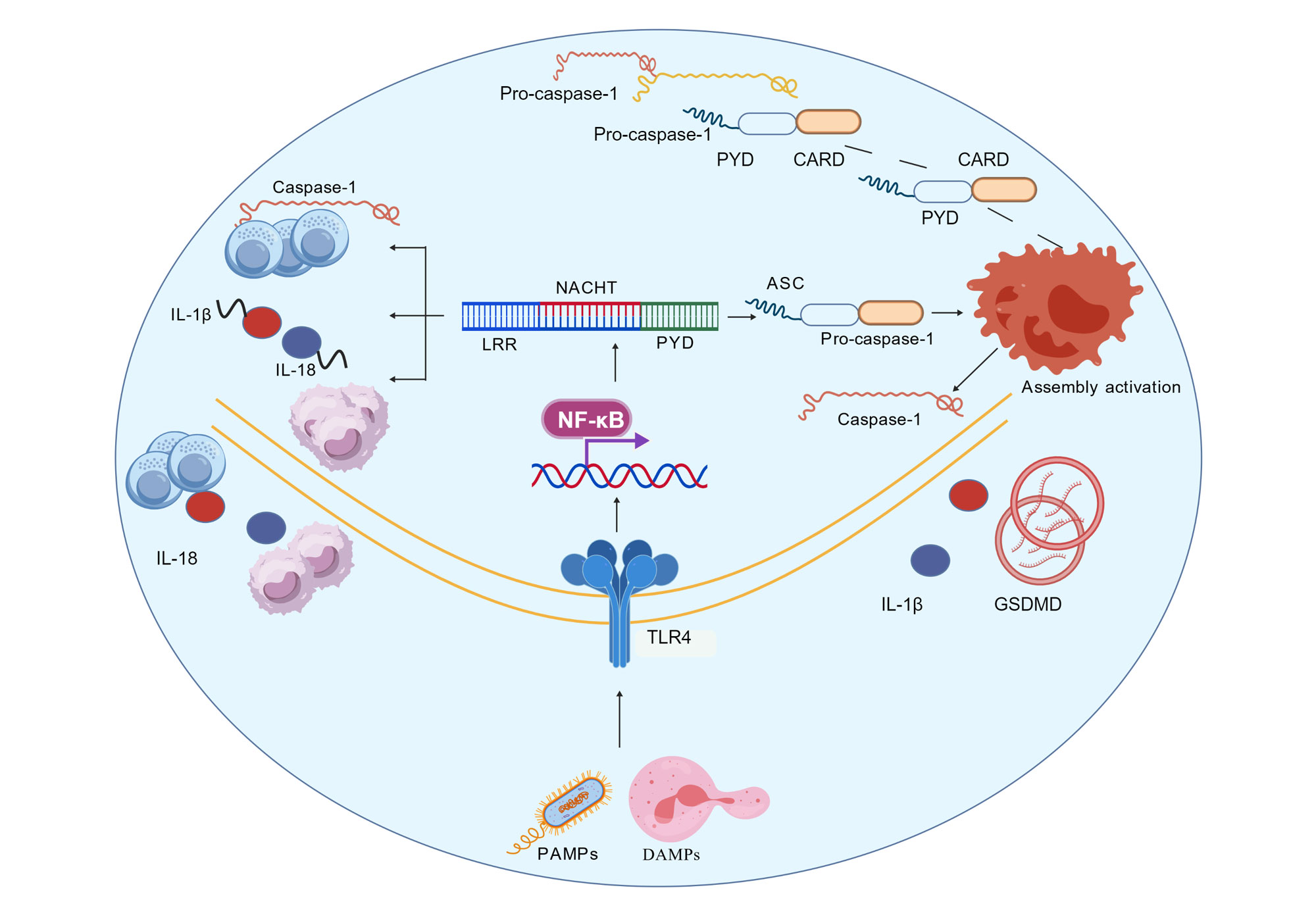

The NLRP3 inflammasome serves as a crucial complex of several proteins in the intrinsic immune reaction, which is mostly made up of NLRP3, the junction protein ASC (CARD-containing apoptosis-associated speck-like protein), and the effector protein caspase-1 [15]. Its main function is to detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), both intracellularly and extracellularly, and to trigger the generation of inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β and IL-18, and mediate the process of cellular pyrokinesis through the activation of caspase-1.

(1) NLRP3, As a receptor protein for inflammatory vesicles, NLRP3 triggers the assembly of inflammatory vesicles by recognizing PAMP and DAMP signals through its LRR (leucine-rich repeat) structural domain. NLRP3 contains three major structural domains: the NACHT structural domain (regulates oligomerization of NLRP3), the LRR structural domain (responsible for sensory signals), and the PYD (a pyrin structural domain mediating interaction with ASC) [16]. When cells are stimulated endogenously and exogenously, NLRP3 undergoes conformational changes through these structural domains, activating the formation of inflammatory vesicles.

(2) ASC, ASC functions as an adaptor protein with PYD and CARD motifs (caspase-activating structural domain) [17]. Its PYD interacts with the PYD structural region of NLRP3 and promotes the aggregation of inflammatory vesicles, while the CARD structural domain activates caspase-1 by attaching itself to the CARD domain of caspase-1, thereby initiating downstream inflammatory responses [18].

(3) Caspase-1, Caspases are effector proteins that are activated when NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles are transformed into their active state. Activated caspase-1 produces a strong immune reaction through the proteolytic processing of precursor molecules IL-1β and IL-18, prompting their maturation and secretion [19]. Caspase-1 additionally triggers pyroptosis, a manifestation of programmed inflammatory cell demise, which further enhances the immune response [20].

Mechanism of activation of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles

Increased NLRP3 inflammatory vesicle activity is a multifaceted, multistep, and complex process that begins at the initiation stage (Figure 1), where cells ensure accurate recognition of PAMPs via intracellular NOD-like receptors (NLRs), cell surface Toll-like receptors (TLRs), and RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), as well as DAMPs via diverse pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as bacterial lipopolysaccharide and viral RNA [13], and DAMPs such as ATP released by cellular damage and uric acid crystals [21, 22]. This recognition process triggers a signaling cascade involving the mobilization and stimulation of adaptor proteins (MyD88, TRIF) and kinases (IRAKs, TBK1), which in turn activate the IKK complex, causing the NF-κB inhibitory protein IκB to be phosphorylated and subsequently degraded. This leads to the relocation of the released NF-κB dimer to the nucleus, where it binds to specific DNA sequences to initiate the transcription of inflammatory genes, including NLRP3, precursor IL-1, IL-18, and others [23]. The newly synthesized NLRP3 protein undergoes a variety of post-translational modifications, such as ubiquitination and phosphorylation, which precisely modulate the stability and activity of NLRP3 and establish the groundwork for the activation of inflammatory vesicles.

During the activation phase, NLRP3 senses PAMPs and DAMPs through its LRR structural domain, inducing conformational changes that promote oligomerisation. Oligomerised ASC is recruited with NLRP3 via PYD-PYD interactions to form macromolecular complexes known as specks [24]. The CARD structural domain of ASC increases the recruitment and activation of caspase-1; then the precursor molecules IL-1 and IL-18 are cleaved by activated caspase-1, leading them to become mature cytokines involved in the inflammatory response, which ultimately activate the immune system through secretion to the outside of the cell [19, 25]. This process has been intensively studied at the molecular level, revealing the complexity of the inflammatory reactions and highlighting the potential to develop treatment approaches for associated disorders.

Function of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles

The NLRP3 inflammatory vesicle serves a significant contribution to the intrinsic immunological reaction as a pivotal element of the intrinsic immune system. Through caspase-1 activation, it facilitates the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-18. IL-1β, as a key factor within the inflammatory process cascade, activates a variety of cells involved in immunity and induces other pro-inflammatory factors, thereby triggering and amplifying the inflammatory response [26]. IL-18, on the other hand, acts synergistically with IL-12 to promote Th1 cell differentiation and IFN-γ production, enhance cellular immune responses, and participate in cytokine storm formation [27]. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is also capable of triggering signal transduction cascade reactions, including recruitment and activation of adaptor proteins and kinases, causing the phosphorylation-induced breakdown of the NF-κB inhibitory protein IκB, which further initiates transcription of inflammation-associated genes and amplifies the inflammatory response [13]. In neurodegenerative diseases, it promotes neuroinflammatory responses and neuronal cell death, resulting in cognitive deterioration and disease progression.

An essential function of NLRP3 inflammasome engagement is to facilitate cellular pyroptosis, a unique type of programmed cell death characterized by membrane rupture and widespread release of inflammatory mediators. This process begins with caspase-1 activation mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome. Mobilised and activated caspase-1 cleaves and activates not only the precursor forms of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, but also gasdermin D (GSDMD) [28]. The N-terminal structural domain of GSDMD has membrane-perforating activity, forming pores within the cellular membrane, resulting in rupture of the cell membrane and discharge of intracellular components, such as IL-1β, IL-18, and other inflammatory mediators [29]. These released factors mobilize and stimulate immune cells and enhance the local immune response, thereby effectively clearing infected cells and initiating adaptive immunity.

However, overactivation of cellular pyroptosis may trigger tissue damage and is related to numerous inflammatory disorders, such as AD, diabetes, and arthritis. In AD, excessive cellular pyroptosis is associated with neuroinflammatory responses and neuronal death, which may lead to cognitive decline.

Figure 1. NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its function in immune response. NLRP3 recognizes damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and recruits pro-caspase-1 through NACHT, LRR, and PYD domains by binding to apoptosis-associated speck-like protein ASC, forming inflammasome complexes and activating caspase-1. Activated caspase-1 cleaves the precursors of IL-1β and IL-18, causing them to mature and be released, thereby mediating inflammatory responses. In addition, NF-κB can regulate the expression of NLRP3 and participate in the regulation of this process. NLRP3: NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; ASC: apoptosis-associated speck-like protein; caspase-1: cysteine-aspartic protease 1; IL-1β: interleukin-1 beta; IL-18: interleukin-18; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-B; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; PAMPs: pathogen-associated molecular patterns.

Figure 1. NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its function in immune response. NLRP3 recognizes damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and recruits pro-caspase-1 through NACHT, LRR, and PYD domains by binding to apoptosis-associated speck-like protein ASC, forming inflammasome complexes and activating caspase-1. Activated caspase-1 cleaves the precursors of IL-1β and IL-18, causing them to mature and be released, thereby mediating inflammatory responses. In addition, NF-κB can regulate the expression of NLRP3 and participate in the regulation of this process. NLRP3: NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; ASC: apoptosis-associated speck-like protein; caspase-1: cysteine-aspartic protease 1; IL-1β: interleukin-1 beta; IL-18: interleukin-18; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-B; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; PAMPs: pathogen-associated molecular patterns.

NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles and beta-amyloid accumulation

Beta-amyloid (Aβ) is produced by an enzymatic pathway from amyloid precursor protein (APP). The first enzyme to process APP is β-secretase, producing soluble APPβ and a C-terminal fragment containing Aβ. Subsequently, the C-terminal fragment is processed by γ-secretase, producing Aβ [30]. Aβ mainly appears in two forms, Aβ40 and Aβ42, with Aβ42 having a stronger tendency to aggregate, resulting in the formation of amyloid plaques, and the deposition of these plaques in the brain is one of the hallmark pathological features of AD [31].

Accumulation and plaque formation of β-amyloid (Aβ) are considered hallmark features of AD, and β-plaque formation not only directly affects neuronal function but also induces a strong immune response. In AD patients, Aβ is considered to be a major determinant initiating the stimulation of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles [32]. Research findings have indicated that Aβ can trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation through multiple pathways, thereby inducing a neuroinflammatory response. For example, Nakanishi et al. explored the interaction of amyloid (Aβ) with NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles by preparing three forms of amyloid (Aβ): monomeric units, oligomeric complexes, and fibrillar aggregates. The results showed that Aβ oligomers and fibers were able to interact directly with NLRP3 and promoted the association of NLRP3 with ASC, which activated the NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles, whereas Aβ monomers did not show such interactions. It was also confirmed that Aβ oligomers and fibers triggered the secretion of IL-1 in cell-based analyses [33].

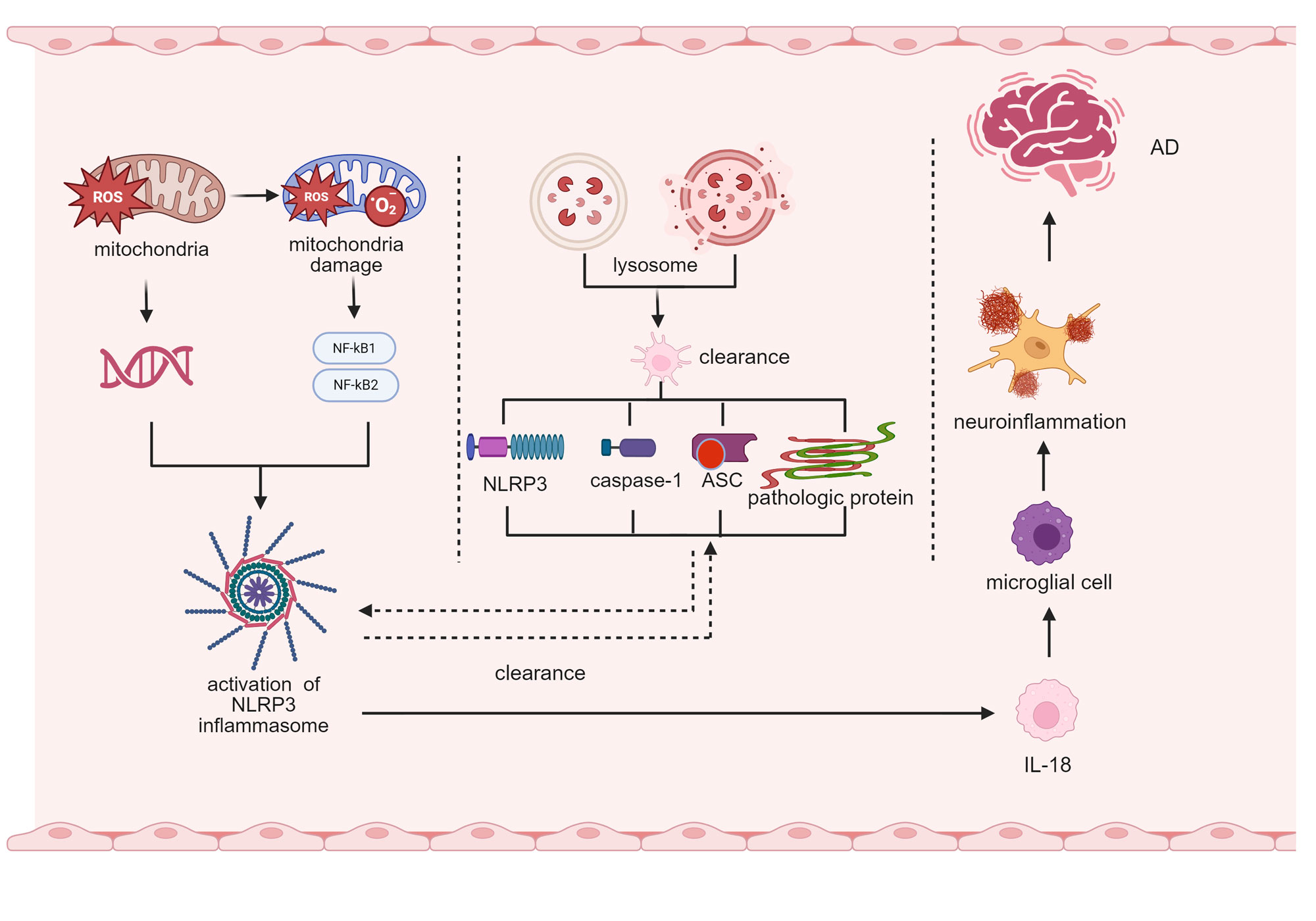

Autophagy not only serves a critical function in the metabolic processes of normal cells, but is also intimately linked to the emergence of certain neurodegenerative illnesses [34]. Especially in neurodegenerative disorders such as AD, dysfunction of autophagy is thought to be an important cause of excessive buildup of Aβ and tau protein. Normally, Aβ is degraded by clearance mechanisms in the brain, but in AD patients, the removal process of Aβ is blocked, leading to its gradual accumulation in the brain and the formation of amyloid plaques [34]. A complex interrelationship exists between autophagy and NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles (Figure 2). Xu et al. showed that the absence of EPO receptors elevated peripheral and brain Aβ levels in peripheral macrophages and worsened brain lesions and behavioral abnormalities in AD model mice. Further studies have found that erythropoietin (EPO) increases phagocytic activity, Aβ-degrading enzyme levels, and PPARγ-mediated Aβ clearance in peripheral macrophages. It also inhibits Aβ-induced inflammation [35]. In addition, Wang et al.'s study revealed that palmitoylation modification of NLRP3 inhibits excessive inflammatory responses by promoting its recognition by the molecular chaperone HSP90, which is then degraded via the CMA (chaperone-mediated autophagy) pathway. In AD models, blocking palmitoylation leads to NLRP3 accumulation and exacerbates Aβ-induced neuroinflammation [36]. A marked rise in Aβ deposition in the cerebral tissues following knockout of macrophage EPO receptors also suggests a key influence of the peripheral clearance system in AD pathology [35].

NLRP3 inflammasome and neuroinflammation

A major pathogenic defining aspect of AD is neuroinflammation, which is intimately linked to disease progression. NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles serve as a significant driver in the progression of neuroinflammation. Inflammatory mediator maturation and release of IL-18, IL-1β, and TNF-α are facilitated by an activated NLRP3 inflammasome by recruiting and activating caspase-1, which in turn triggers a neuroinflammatory response [37]. These factors not only enhance the localized inflammatory response, but may also further damage neurons and promote neurodegenerative changes. This inflammatory response helps to clear pathogens and damaged cells in the short term, but prolonged or excessive inflammatory responses lead to neuronal damage, glial cell activation, and neural circuit dysfunction, which take part in the pathology of several neurological degenerative disorders [38].

Activation of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles involves multiple upstream signaling pathways, including TLR and NF-κB, which influence the activity of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles by harmonizing NLRP3 gene expression and post-translational protein modifications [39]. For example, Guo et al. found that the phosphatase SHP2 translocated to mitochondria and interacted with ANT1 to mediate fine regulation of homeostasis in NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles, which provided a fresh viewpoint for understanding the regulatory operations of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles [40]. In addition, Zhang et al. showed that isocyanic acid, a naturally occurring metabolite, and its induced NLRP3 carbamoylation can suppress the activation of the inflammasome and the NLRP3-NEK7 interaction, providing a new strategy for inflammation regulation. At the molecular level, isocyanic acid interacts directly with and modifies NLRP3 through carbamoylation at the lysine-593 residue, thereby disrupting the NLRP3-NEK7 interaction, which is a crucial step in the establishment of active NLRP3 inflammasomes [41].

Yin et al. reported tilianin as a suppressor of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and protected cardiomyocytes from ischemia-reperfusion damage by blocking the NEK7/NLRP3 interface and the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway [42], which also provided a novel approach for managing AD. Li et al. found that minocycline may partly mediate the microglia polarization process and restoration of synaptic plasticity through the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway, boost neuronal viability, and reestablish synaptic plasticity, thus mitigating TN-related cognitive decline [43]. In addition, downstream inflammatory signaling molecules such as IL-1β and IL-18 further increase the inflammatory response through autocrine and paracrine modes, creating a positive feedback loop [44]. This positive feedback loop is essential in various neurodegenerative conditions; for example, in AD, Aβ amyloid activates NLRP3 inflammasome, which in turn promotes neuroinflammation and neuronal damage [45]. Therefore, targeting both upstream and downstream NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathways has become a new strategy to regulate neuroinflammation and treat related diseases.

In summary, NLRP3 inflammasome serves as a pivotal component in the initiation and modulation of neuroinflammation, and its complex regulatory network provides rich targets for the development of novel treatment approaches. Future research ought to concentrate more on the relationship of NLRP3 inflammasome with other pathological mechanisms, with the aim of providing more comprehensive and effective strategies for the treatment of neuroinflammation-related diseases.

Functions of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles and microglia

The resident immune cells in the brain are called microglia, which are essential to the course of AD. Microglial cells in the brains of AD sufferers are usually in a state of continuous activation, and they regulate the brain's immunological reaction by releasing large amounts of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines through NLRP3 inflammatory vesicle activation [46].

McManus et al. found in mice that deletion of NLRP3 enhanced the metabolism of glutamine and glutamate and increased microglial Slc1a3 expression, a process in which α-ketoglutarate production affected cellular functions, including increased Aβ peptide clearance and epigenetic and gene transcription changes [47]. When AD is just beginning, microglial cells try to remove Aβ deposits, but with continued activation of the inflammatory response, microglial cells become overactivated and release large amounts of harmful factors. Baligács et al. found that at the early stages of AD, microglial cells are not yet activated and mostly preserve homeostasis; later in the disease, they become active and remove Aβ plaques from the brain. However, after plaque formation, activated microglia may make plaques tighter and reduce neuronal pathology [48]. Flury et al. identified an evolutionarily conserved stress response signaling pathway, the integrated stress response (ISR) that distinguishes a subset of microglia with detrimental effects. The results showed that early characteristics of ultrastructurally different “dark microglia” can be induced by ISR in autonomously activated microglia and are associated with pathological synaptic loss. Microglial ISR activation in AD models exacerbated neurodegenerative disease and synaptic loss, whereas its inhibition ameliorated them [49]. These findings suggest that ISR pathway activation in microglia may represent a novel neurodegenerative phenotype maintained partially through the release of harmful lipids, providing potential therapeutic avenue.

Overactivated microglia may promote neuronal damage and the development of neurodegenerative pathologies. In addition, NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles affect affect the functioning of microglial cells as well as of other neuroglia, such as astrocytes [50], which ultimately contributes to inflammatory responses and degenerative changes in the nervous system. There is increasing interest in astrocyte function in AD, as astrocytes indirectly influence disease progression by participating in immune responses, removing waste products, and supporting neuronal survival. Recent studies have revealed significant cell type-dependent NLRP3 inflammatory vesicle activation in AD. Microglia, as the mainstay of central immunity, were shown by Heneka et al. to exhibit NLRP3 activation mainly triggered by Aβ oligomers via TLR4/MyD88 signaling [51]. In contrast, NLRP3 activation in astrocytes is closely associated with tau protein phosphorylation and mitochondrial DNA leakage. Li et al. found that microglial NLRP3 drives astrocyte conversion to a neurotoxic A1 phenotype via the NF-κB/caspase-1 axis in a chronic stress-induced model of depression [52], suggesting that cross-talk between these two types of glial cells may exacerbate synaptic loss in AD.

Figure 2. The function of the NLRP3 inflammasome in neuroinflammation in AD. The functional mechanism of the NLRP3 inflammasome in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) neuropathy is demonstrated. It displays mitochondrial damage, such as generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), release of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and regulation of inflammasome activation through the NF-κB1/NF-κB2 signaling pathway, and reflects abnormal lysosomal clearance and development of inflammasome complexes composed of NLRP3, caspase-1, and ASC. Simultaneously, it presents a cascade reaction of neuroinflammation, involving microglia activation and IL-18 release, ultimately leading to the occurrence of AD. Overall, it reveals the key driving role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathological process of AD. AD: Alzheimer’s disease; ROS: reactive oxygen species; mtDNA: mitochondrial DNA; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-B subunit 1; NF-κB2: nuclear factor kappa-B subunit 2; NLRP3: NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; caspase-1: cysteine-aspartic protease 1; ASC: apoptosis-associated speck-like protein; IL-18: interleukin-18.

Figure 2. The function of the NLRP3 inflammasome in neuroinflammation in AD. The functional mechanism of the NLRP3 inflammasome in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) neuropathy is demonstrated. It displays mitochondrial damage, such as generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), release of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and regulation of inflammasome activation through the NF-κB1/NF-κB2 signaling pathway, and reflects abnormal lysosomal clearance and development of inflammasome complexes composed of NLRP3, caspase-1, and ASC. Simultaneously, it presents a cascade reaction of neuroinflammation, involving microglia activation and IL-18 release, ultimately leading to the occurrence of AD. Overall, it reveals the key driving role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathological process of AD. AD: Alzheimer’s disease; ROS: reactive oxygen species; mtDNA: mitochondrial DNA; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-B subunit 1; NF-κB2: nuclear factor kappa-B subunit 2; NLRP3: NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; caspase-1: cysteine-aspartic protease 1; ASC: apoptosis-associated speck-like protein; IL-18: interleukin-18.

Targeted therapy of NLRP3 inflammasome

Small molecule inhibitors are one of the most promising therapeutic strategies currently available. MCC950 is among the most selective NLRP3 inhibitors known to block the activation of NLRP3 by directly interacting with it, thereby inhibiting the assembly of inflammatory vesicles. The results of Coll et al.’s study showed that MCC950 blocked both classical and nonclassical NLRP3 activation and specifically suppressed NLRP3 activation, but not AIM2, NLRC4, or NLRP1 inflammatory vesicles [53]. MCC950 also reduced IL-1β production in vivo and lessened experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) severity, a multiple sclerosis model [53].

For AD, MCC950 inhibited the release of IL-1β and activation of caspase-1 induced by LPS + Aβ in microglia without inducing pyroptosis, according to Dempsey et al. MCC950 also inhibited APP/PS1 inflammatory vesicle activation and microglial activation in AD, as demonstrated in a murine model [54]. In addition, MCC950 enhanced Aβ clearance and reduced Aβ accumulation in the APP/PS1 mouse model in vitro, suggesting an association with improved cognitive function [54]. Naeem et al. administered MCC950 intraperitoneally (50 mg/kg body weight) to rats (3 mg/kg body weight) with AD-like symptoms induced by intracerebral injections of streptozotocin (STZ). MCC950 effectively alleviated STZ-induced cognitive deficits and anxiety by blocking the NLRP3-mediated neuroimmune response [55]. This finding suggests that MCC950 reduces autophagy in neural cells to promote neuroprotection.

MCC950 and similar small molecule inhibitors have been extensively studies in recent years. Some of this research has indicated that these inhibitors can significantly reduce β-amyloid accumulation, neuroinflammation, and activation of microglial cells in AD mouse models. For example, according to Chen et al., compound 32 (ZJCK-6-46) was identified as the most promising DYRK1A inhibitor (IC₅₀ = 0.68 nM). Compound 32 considerably decreased p-Tau Thr212 expression in Tau (P301L) 293T cells and SH-SY5Y cells, while demonstrating adequate absorbance, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) characteristics in vitro [56]. Furthermore, by dramatically lowering phosphorylated tau expression and neuronal cell loss in vivo, compound 32 may lead to improvements in cognitive impairment and shows good bioavailability and blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability. According to Guo et al.’s study, IsoLiPro, a special lithium isobutyrate-L-proline ligand, improved tau ubiquitination and successfully decreased USP11 protein levels in vitro. In addition, in AD transgenic mice, IsoLiPro has been shown to inhibit total as well as phosphorylated tau proteins, β-amyloid deposition and synaptic damage and promote cognitive function in these animals [57]. Despite small molecule inhibitors have shown favorable results in laboratory studies, their ability to effectively cross the BBB and achieve clinical efficacy still requires further research and validation. In addition, compounds, such as CSB6B [58], BHB [59], Melatonin [60], D4T [61], AIH [62], TSG [63], ECH [64], DHM [65], PG [66] and other compounds all inhibit inflammatory vesicle activation by the mechanisms described in Table 1.

In addition to small-molecule inhibitors, biologics (e.g., monoclonal antibodies) targeting NLRP3 are moving into preclinical studies. Sevigny et al. reported that a human monoclonal antibody named aducanumab, which specifically targets aggregated Aβ aducanumab, penetrates the blood-brain barrier in a transgenic mouse model of AD, bind to parenchymal Aβ, and decrease both soluble and insoluble Aβ [67]. Christopher et al. applied lecanemab and found that it slowed the decline in CDR-SB scores by 27% and significantly reduced cerebrospinal fluid p-Tau181 and plasma GFAP levels in patients with early-stage AD over 18 months of treatment, confirming that it attenuates neurodegeneration by removing Aβ protofibrils [68]. Biologics may have higher targeting and specificity compared to small molecule drugs, but their ability to cross the BBB remains a challenge.

Options for traditional Chinese medicine treatment

In recent years, several natural products and plant compounds have shown inhibitory effects on NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles. For example, Monkey head fungus has antioxidant activity. Cordaro et al. reported that, in a preclinical AD model induced by administration of AlCl₃, Monkey head fungus inhibited the initiation of NLRP3 inflammatory vesicle activity by increasing the expression of Nrf2 in hippocampal tissues of rats, enhancing the activities of SOD and GSH, and thus reducing hippocampal neuronal degeneration and improving behavior in rats [69]. Mangiferin, a polyphenol obtained from the plant, has demonstrated inflammation-reducing and free radical-scavenging properties, as well as antibacterial properties. Yan et al. used LPS stimulation to construct a BV2 cell model and found that it greatly decreased the release of inflammatory substances such as NO, IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, lowered iNOS and COX-2 gene mRNA and protein expression, and facilitated the classification of microglia toward an anti-inflammatory state, while blocking the activation of the NLRP3 and NF-κB signaling pathways [70]. According to these results, mangiferin might be a viable natural treatment option for neuroinflammatory conditions.

Rhodioloside, the key bioactive substance extracted from Rhodiola rosea, was demonstrated by Cai et al. to inhibit NLRP3 inflammatory vesicle-mediated pyroptosis and protect neurons. Its potential mechanism is regulation of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway, inhibition of ASC and cleaved caspase-1 expression, reduction of Aβ and tau protein aggregation, and ultimately reduction of hippocampal neuronal damage [71]. In addition, Li et al. found that baicalin (BA) inhibited LPS-induced neuroinflammation in BV-2 microglia by suppressing the production of miR-155 and blocking signaling mediated by the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB and MAPK signaling cascades [72], which suggests that BA might be a useful therapeutic strategy for treating neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory diseases.

Active lychee seed fraction rich in polyphenols (LSP) exhibited Aβ-induced anti-inflammatory effects in BV-2 cells. Qiu et al. showed that an active lychee seed fraction rich in LSP inhibited NLRP3 inflammatory vesicle-mediated neuroinflammation in an AD model by activating autophagy in microglia [73]. The specific mode of action was that LSP markedly inhibited the Aβ-induced neuroinflammatory response and improved cognitive function in APP/PS1 mice by upregulating LRP1 and its associated AMPK-mediated signaling cascade [73]. In addition, the Chinese herbal formula Paeonia lactiflora and Glycyrrhiza glabra Tang may also inhibit neuroinflammation by mediating oxidative stress. Ultimately, by repairing synaptic plasticity, these natural products may become new adjunctive therapeutic strategies in addition to traditional drug therapy.

|

Table1. Compounds modulating inflammation and their effects on neurodegenerative diseases. |

||

|

Compound name |

Action effect |

References |

|

CSB6B

|

Counteracts cognitive dysfunction and neuroinflammation induced by Aβ via inhibiting NF-κB and NLRP3 pathways |

[58] |

|

BHB |

Decreases plaque accumulation, and microglial and caspase-1 activation observed in 5XFAD animal model of AD |

[59] |

|

Melatonin |

Inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation and significantly reduces the concentrations of IL-18 and IL-1β |

[60] |

|

D4T |

Downregulates the generation of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 β, IL-18, and Caspase-1) and decreases the expression of Caspase-3 |

[61] |

|

AIH |

Suppresses LPS-induced nitric oxide (NO) and downregulates inducible NO synthase, cyclooxygenase-2, TNF-α, and interleukin-6 |

[62] |

|

TSG

|

Enhances mitochondrial autophagy through AMPK/PINK1/Parkin dependence to prevent LPS/ATP and Aβ-induced inflammation |

[63] |

|

ECH

|

Inhibits the deposition of Aβ in the PI3K/AKT/Nrf2/PPAR γ signaling pathway |

[64] |

|

DHM

|

Reduces stimulation of NLRP3 inflammasome and the expression of its components. Converts microglia into M2 specific positive cell phenotype to promote the clearance of A β |

[65] |

|

PG |

Suppresses Aβ-induced the NLRP3-Caspase-1 inflammasome activation |

[66] |

|

CSB6B, chicago sky blue 6B; BHB, butropium bromide; D4T, stavudine; AIH, aluminum hydride; TSG, 2,3,5,4'-tetrahydroxystilbene-2-O-β-D-glucopyranoside; ECH, epichlorohydrin; DHM, dihydromyricelin; PG, propylene glycol. |

||

Considering the multifactorial pathological characteristics of AD, single-targeted therapy may have limited effectiveness. Therefore, future treatment strategies may need to combine NLRP3 inhibitors with other drugs, such as antioxidants, neuroprotective agents, or anti-beta-amyloid drugs, to more effectively control disease progression and improve clinical symptoms through multiple interventions. Although treatment approaches targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome have potential, they still face multiple challenges. The most prominent issue is how to overcome the BBB, a natural barrier, to ensure that therapeutic drugs can effectively reach the brain. At present, innovative technologies such as nanomedicine carriers are becoming a research focus to address this problem. In addition, long-term use of NLRP3 inhibitors might impair the normal functioning of the immune system. Therefore, when developing therapies, careful consideration must be given to balancing efficacy with maintenance of immune function to avoid adverse reactions. Recently, natural products have shown potential in regulating NLRP3 inflammasomes. For example, plant-based compounds such as Hericium erinaceus and mangiferin have demonstrated inhibitory effect on the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Hence, these compounds offer a novel approach to manage AD, and support adjuvant therapy alongside traditional therapeutics.

In summary, NLRP3 inflammasome’s involvement in neuroinflammatory responses and neurodegenerative changes is a key mechanism in AD. Hence, targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome to alleviate neuroinflammation is a promsing strategy to treat AD, despite current challenges involving drug delivery and long-term safety. Studies must focus on NLRP3 inflammasome’s crosstalk with pathological mechanisms in future, with the aim to provide more comprehensive and effective strategies to tackle AD.

No applicable.

Ethics approval

No applicable.

Data availability

The data will be available upon request.

Funding

This review was supported by the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province (No. 2023-ZDLSF-57).

Authors’ contribution

Yanhua Wang wrote the drafted article; Hua Li created the tables and charts.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

- Olivari B, Taylor C, Reed N, McGuire L: Promoting Conversations About Cognitive Decline Between Older Adults and Primary Care Providers. Innovation in Aging 2020, 4: 157-158.

- Wu XR, Zhu XN, Pan YB, Gu X, Liu XD, Chen S, Zhang Y, Xu TL, Xu NJ, Sun S: Amygdala neuronal dyshomeostasis via 5‐HT receptors mediates mood and cognitive defects in Alzheimer's disease. Aging Cell 2024, 23(8): e14187.

- Scheltens P, De Strooper B, Kivipelto M, Holstege H, Chételat G, Teunissen CE, Cummings J, van der Flier WM: Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 2021, 397(10284): 1577-1590.

- Christensen D, Kraus S, Flohr A, Cotel M, Wirths O, Bayer T: Transient intraneuronal Aβ rather than extracellular plaque pathology correlates with neuron loss in the frontal cortex of APP/PS1KI mice. Acta Neuropathologica 2008, 116(6): 647-655.

- Xue Z: Neuroinflammation as a core pathogenic mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease: recent research advances and related therapeutical approaches. ICBioMed 2022, 12611: 126111-126111.

- Kaur D, Sharma V, Deshmukh R: Activation of microglia and astrocytes: a roadway to neuroinflammation and Alzheimer's disease. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27(4): 663-677.

- Kaur D, Sharma V, Deshmukh R: Activation of microglia and astrocytes: a roadway to neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27(4): 663-677.

- Fischer R, Maier O: Interrelation of oxidative stress and inflammation in neurodegenerative disease: role of TNF. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015, 2015: 610813.

- Zhang H, Wei W, Zhao M, Ma L, Jiang X, Pei H, Cao Y, Li H: Interaction between Aβ and Tau in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Biol Sci 2021, 17(9): 2181-2192.

- Fang L, Shen S, Liu Q, Liu Z, Zhao J: Combination of NSAIDs with donepezil as multi-target directed ligands for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2022, 75: 128976.

- Xia P, Chen J, Liu Y, Cui X, Wang C, Zong S, Wang L, Lu Z: MicroRNA-22-3p ameliorates Alzheimer's disease by targeting SOX9 through the NF-κB signaling pathway in the hippocampus. J Neuroinflammation 2022, 19(1): 180.

- Mamun AA, Shao C, Geng P, Wang S, Xiao J: Polyphenols Targeting NF-κB Pathway in Neurological Disorders: What We Know So Far? Int J Biol Sci 2024, 20(4): 1332-1355.

- Ramachandran R, Manan A, Kim J, Choi S: NLRP3 inflammasome: a key player in the pathogenesis of life-style disorders. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2024, 56(7): 1488-1500.

- McManus RM, Komes MP, Griep A, Santarelli F, Schwartz S, Perea J, Khalil M-A, Schlachetzki JCM, Bouvier DS, Lauterbach M et al: NLRP3 regulates immunometabolism, impacting microglial function in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Dement 2024, 20(S8): e095562.

- No authors listed: Innate immune barrier against oncogenic transformation. Nat Immunol 2025, 26(1): 13-14.

- Xiao L, Magupalli VG, Wu H: Cryo-EM structures of the active NLRP3 inflammasome disc. Nature 2023, 613(7944): 595-600.

- Hochheiser IV, Behrmann H, Hagelueken G, Rodríguez-Alcázar JF, Kopp A, Latz E, Behrmann E, Geyer M: Directionality of PYD filament growth determined by the transition of NLRP3 nucleation seeds to ASC elongation. Sci Adv 2022, 8(19): eabn7583.

- Martín-Sánchez F, Compan V, Peñín-Franch A, Tapia-Abellán A, Gómez AI, Baños-Gregori MC, Schmidt FI, Pelegrin P: ASC oligomer favors caspase-1CARD domain recruitment after intracellular potassium efflux. J Cell Biol 2023, 222(8): e202003053.

- Dong Y, Bonin JP, Devant P, Liang Z, Sever AIM, Mintseris J, Aramini JM, Du G, Gygi SP, Kagan JC et al: Structural transitions enable interleukin-18 maturation and signaling. Immunity 2024, 57(7): 1533-1548.e1510.

- Arakelian T, Oosterhuis K, Tondini E, Los M, Vree J, van Geldorp M, Camps M, Teunisse B, Zoutendijk I, Arens R et al: Pyroptosis-inducing active caspase-1 as a genetic adjuvant in anti-cancer DNA vaccination. Vaccine 2022, 40(13): 2087-2098.

- Xu Z, Kombe Kombe AJ, Deng S, Zhang H, Wu S, Ruan J, Zhou Y, Jin T: NLRP inflammasomes in health and disease. Mol Biomed 2024, 5(1): 14.

- Ma M, Jiang W, Zhou R: DAMPs and DAMP-sensing receptors in inflammation and diseases. Immunity 2024, 57(4): 752-771.

- Paik S, Kim JK, Silwal P, Sasakawa C, Jo EK: An update on the regulatory mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Mol Immunol 2021, 18(5): 1141-1160.

- Zheng D, Liwinski T, Elinav E: Inflammasome activation and regulation: toward a better understanding of complex mechanisms. Cell Discov 2020, 6: 36.

- Huang X, Zhao Z, Zhu C, Chai L, Yan Y, Yuan Y, Wu L, Li M, Jiang X, Wang H et al: Species-specific IL-1β is an inflammatory sensor of Seneca Valley Virus 3C Protease. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20(7): e1012398.

- Hanamsagar R, Torres V, Kielian T: Inflammasome activation and IL-1β/IL-18 processing are influenced by distinct pathways in microglia. J Neurochem 2011, 119(4): 736-748.

- Gleeson TA, Nordling E, Kaiser C, Lawrence CB, Brough D, Green JP, Allan SM: Looking into the IL-1 of the storm: are inflammasomes the link between immunothrombosis and hyperinflammation in cytokine storm syndromes? Discov Immunol 2022, 1(1): kyac005.

- Zheng X, Wan J, Tan G: The mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome/pyroptosis activation and their role in diabetic retinopathy. Front Immunol 2023, 14: 1151185.

- Wang C, Yang T, Xiao J, Xu C, Alippe Y, Sun K, Kanneganti TD, Monahan JB, Abu-Amer Y, Lieberman J, Mbalaviele G: NLRP3 inflammasome activation triggers gasdermin D-independent inflammation. Sci Immunol 2021, 6(64): eabj3859.

- Hampel H, Hardy J, Blennow K, Chen C, Perry G, Kim SH, Villemagne VL, Aisen P, Vendruscolo M, Iwatsubo T et al: The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26(10): 5481-5503.

- Hanaki M, Murakami K, Akagi K, Irie K: Structural insights into mechanisms for inhibiting amyloid β42 aggregation by non-catechol-type flavonoids. Bioorg Med Chem 2016, 24(2): 304-313.

- Gao X, Zhang X, Sun Y, Dai X: Mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its role in Alzheimer's disease. Explor Immunol 2022, 2(3): 229-244.

- Nakanishi A, Kaneko N, Takeda H, Sawasaki T, Morikawa S, Zhou W, Kurata M, Yamamoto T, Akbar SMF, Zako T, Masumoto J: Amyloid β directly interacts with NLRP3 to initiate inflammasome activation: identification of an intrinsic NLRP3 ligand in a cell-free system. Inflamm Regen 2018, 38(1): 27.

- Palmer JE, Wilson N, Son SM, Obrocki P, Wrobel L, Rob M, Takla M, Korolchuk VI, Rubinsztein DC: Autophagy, aging, and age-related neurodegeneration. Neuron 2025, 113(1): 29-48.

- Xu L, Li L, Pan CL, Song JJ, Zhang CY, Wu XH, Hu F, Liu X, Zhang Z, Zhang ZY: Erythropoietin signaling in peripheral macrophages is required for systemic β-amyloid clearance. EMBO J 2022, 41(22): e111038.

- Wang L, Cai J, Zhao X, Ma L, Zeng P, Zhou L, Liu Y, Yang S, Cai Z, Zhang S et al: Palmitoylation prevents sustained inflammation by limiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation through chaperone-mediated autophagy. Molecular Cell 2023, 83(2): 281-297.e210.

- Jha D, Bakker E, Kumar R: Mechanistic and therapeutic role of NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem 2024, 168(10): 3574-3598.

- Blevins HM, Xu Y, Biby S, Zhang S: The NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway: A Review of Mechanisms and Inhibitors for the Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14: 879021.

- Kodi T, Sankhe R, Gopinathan A, Nandakumar K, Kishore A: New Insights on NLRP3 Inflammasome: Mechanisms of Activation, Inhibition, and Epigenetic Regulation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2024, 19(1): 7.

- Guo W, Liu W, Chen Z, Gu Y, Peng S, Shen L, Shen Y, Wang X, Feng GS, Sun Y, Xu Q: Tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 negatively regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation via ANT1-dependent mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat Commun 2017, 8(1): 2168.

- Zhang Z, Chen C, Liu C, Sun P, Liu P, Fang S, Li X: Isocyanic acid-mediated NLRP3 carbamoylation reduces NLRP3-NEK7 interaction and limits inflammasome activation. Sci Adv 2025, 11(10): eadq4266.

- Yin S, Han K, Wu D, Wang Z, Zheng R, Fang L, Wang S, Xing J, Du G: Tilianin suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via inhibition of TLR4/NF-κB and NEK7/NLRP3. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15: 1423053.

- Li J, Mi X, Yang Z, Feng Z, Han Y, Wang T, Lv H, Liu Y, Wu K, Liu J: Minocycline ameliorates cognitive impairment in rats with trigeminal neuralgia by regulating microglial polarization. Int Immunopharmacol 2025, 145: 113786.

- Demirtaş N, Mazlumoğlu B, Palabıyık Yücelik Ş S: Role of NLRP3 Inflammasomes in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Eurasian J Med 2023, 55(1): 98-105.

- Sharma B, Satija G, Madan A, Garg M, Alam MM, Shaquiquzzaman M, Khanna S, Tiwari P, Parvez S, Iqubal A et al: Role of NLRP3 Inflammasome and Its Inhibitors as Emerging Therapeutic Drug Candidate for Alzheimer's Disease: a Review of Mechanism of Activation, Regulation, and Inhibition. Inflammation 2023, 46(1): 56-87.

- Palomino-Antolín A, Decouty-Pérez C, Farré-Alins V, Narros-Fernández P, Lopez-Rodriguez AB, Álvarez-Rubal M, Valencia I, López-Muñoz F, Ramos E, Cuadrado A et al: Redox Regulation of Microglial Inflammatory Response: Fine Control of NLRP3 Inflammasome through Nrf2 and NOX4. Antioxidants 2023, 12(9): 1729.

- McManus RM, Komes MP, Griep A, Santarelli F, Schwartz S, Ramón Perea J, Schlachetzki JCM, Bouvier DS, Khalil MA, Lauterbach MA et al: NLRP3-mediated glutaminolysis controls microglial phagocytosis to promote Alzheimer's disease progression. Immunity 2025, 58(2): 326-343.e311.

- Baligács N, Albertini G, Borrie SC, Serneels L, Pridans C, Balusu S, De Strooper B: Homeostatic microglia initially seed and activated microglia later reshape amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's Disease. Nat Commun 2024, 15(1): 10634.

- Flury A, Aljayousi L, Park HJ, Khakpour M, Mechler J, Aziz S, McGrath JD, Deme P, Sandberg C, González Ibáñez F et al: A neurodegenerative cellular stress response linked to dark microglia and toxic lipid secretion. Neuron 2025, 113(4): 554-571.e514.

- Kim S, Chun H, Kim Y, Kim Y, Park U, Chu J, Bhalla M, Choi SH, Yousefian-Jazi A, Kim S et al: Astrocytic autophagy plasticity modulates Aβ clearance and cognitive function in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener 2024, 19(1): 55.

- Heneka MT, Kummer MP, Stutz A, Delekate A, Schwartz S, Vieira-Saecker A, Griep A, Axt D, Remus A, Tzeng TC et al: NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer's disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature 2013, 493(7434): 674-678.

- Li S, Fang Y, Zhang Y, Song M, Zhang X, Ding X, Yao H, Chen M, Sun Y, Ding J et al: Microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activates neurotoxic astrocytes in depression-like mice. Cell Reports 2022, 41(4): 111532.

- Coll RC, Robertson AA, Chae JJ, Higgins SC, Muñoz-Planillo R, Inserra MC, Vetter I, Dungan LS, Monks BG, Stutz A et al: A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nat Med 2015, 21(3): 248-255.

- Dempsey C, Rubio Araiz A, Bryson KJ, Finucane O, Larkin C, Mills EL, Robertson AAB, Cooper MA, O'Neill LAJ, Lynch MA: Inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome with MCC950 promotes non-phlogistic clearance of amyloid-β and cognitive function in APP/PS1 mice. Brain Behav Immun 2017, 61: 306-316.

- Naeem A, Prakash R, Kumari N, Ali Khan M, Quaiyoom Khan A, Uddin S, Verma S, Ab Robertson A, Boltze J, Shadab Raza S: MCC950 reduces autophagy and improves cognitive function by inhibiting NLRP3-dependent neuroinflammation in a rat model of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Behav Immun 2024, 116: 70-84.

- Chen H, Gao X, Li X, Yu C, Liu W, Qiu J, Liu W, Geng H, Zheng F, Gong H et al: Discovery of ZJCK-6-46: A Potent, Selective, and Orally Available Dual-Specificity Tyrosine Phosphorylation-Regulated Kinase 1A Inhibitor for the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. J Med Chem 2024, 67(15): 12571-12600.

- Guo Y, Cai C, Zhang B, Tan B, Tang Q, Lei Z, Qi X, Chen J, Zheng X, Zi D et al: Targeting USP11 regulation by a novel lithium-organic coordination compound improves neuropathologies and cognitive functions in Alzheimer transgenic mice. EMBO Mol Med 2024, 16(11): 2856-2881.

- Yan S, Xuan Z, Yang M, Wang C, Tao T, Wang Q, Cui W: CSB6B prevents β-amyloid-associated neuroinflammation and cognitive impairments via inhibiting NF-κB and NLRP3 in microglia cells. Int Immunopharmacol 2020, 81: 106263.

- Shippy DC, Wilhelm C, Viharkumar PA, Raife TJ, Ulland TK: β-Hydroxybutyrate inhibits inflammasome activation to attenuate Alzheimer's disease pathology. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17(1): 280.

- Fan L, Zhaohong X, Xiangxue W, Yingying X, Xiao Z, Xiaoyan Z, Jieke Y, Chao L: Melatonin Ameliorates the Progression of Alzheimer's Disease by Inducing TFEB Nuclear Translocation, Promoting Mitophagy, and Regulating NLRP3 Inflammasome Activity. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2022: 8099459.

- La Rosa F, Zoia CP, Bazzini C, Bolognini A, Saresella M, Conti E, Ferrarese C, Piancone F, Marventano I, Galimberti D et al: Modulation of MAPK- and PI3/AKT-Dependent Autophagy Signaling by Stavudine (D4T) in PBMC of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Cells 2022, 11(14): 2180.

- Ju IG, Huh E, Kim N, Lee S, Choi JG, Hong J, Oh MS: Artemisiae Iwayomogii Herba inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation by regulating NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Phytomedicine 2021, 84: 153501.

- Gao Y, Li J, Li J, Hu C, Zhang L, Yan J, Li L, Zhang L: Tetrahydroxy stilbene glycoside alleviated inflammatory damage by mitophagy via AMPK related PINK1/Parkin signaling pathway. Biochem Pharmacol 2020, 177: 113997.

- Qiu H, Liu X: Echinacoside Improves Cognitive Impairment by Inhibiting Aβ Deposition Through the PI3K/AKT/Nrf2/PPARγ Signaling Pathways in APP/PS1 Mice. Mol Neurobiol 2022, 59(8): 4987-4999.

- Feng J, Wang JX, Du YH, Liu Y, Zhang W, Chen JF, Liu YJ, Zheng M, Wang KJ, He GQ: Dihydromyricetin inhibits microglial activation and neuroinflammation by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. CNS Neurosci Ther 2018, 24(12): 1207-1218.

- Hong Y, Liu Y, Yu D, Wang M, Hou Y: The neuroprotection of progesterone against Aβ-induced NLRP3-Caspase-1 inflammasome activation via enhancing autophagy in astrocytes. Int Immunopharmacol 2019, 74: 105669.

- Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussière T, Weinreb PH, Williams L, Maier M, Dunstan R, Salloway S, Chen T, Ling Y et al: The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2016, 537(7618): 50-56.

- Dyck CHv, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, Bateman RJ, Chen C, Gee M, Kanekiyo M, Li D, Reyderman L, Cohen S et al: Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. 2023, 388(1): 9-21.

- Cordaro M, Salinaro AT, Siracusa R, D'Amico R, Impellizzeri D, Scuto M, Ontario ML, Cuzzocrea S, Di Paola R, Fusco R, Calabrese V: Key Mechanisms and Potential Implications of Hericium erinaceus in NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Reactive Oxygen Species during Alzheimer's Disease. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10(11): 1664.

- Lei L-Y, Wang R-C, Pan Y-L, Yue Z-G, Zhou R, Xie P, Tang Z-S: Mangiferin inhibited neuroinflammation through regulating microglial polarization and suppressing NF-κB, NLRP3 pathway. Chin J Nat Med 2021, 19(2): 112-119.

- Cai Y, Chai Y, Fu Y, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Zhu L, Miao M, Yan T: Salidroside Ameliorates Alzheimer's Disease by Targeting NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated Pyroptosis. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13: 809433.

- Li B, Wang M, Chen S, Li M, Zeng J, Wu S, Tu Y, Li Y, Zhang R, Huang F, Tong X: Baicalin Mitigates the Neuroinflammation through the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB and MAPK Pathways in LPS-Stimulated BV-2 Microglia. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2022: 3263446.

- Qiu WQ, Pan R, Tang Y, Zhou XG, Wu JM, Yu L, Law BY, Ai W, Yu CL, Qin DL, Wu AG: Lychee seed polyphenol inhibits Aβ-induced activation of NLRP3 inflammasome via the LRP1/AMPK mediated autophagy induction. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 130: 110575.

- Wang M, Pan W, Xu Y, Zhang J, Wan J, Jiang H: Microglia-Mediated Neuroinflammation: A Potential Target for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases. J Inflamm Res 2022, 15: 3083-3094.

Asia-Pacific Journal of Pharmacotherapy & Toxicology

p-ISSN: 2788-6840

e-ISSN: 2788-6859

Copyright © Asia Pac J Pharmacother Toxicol. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Copyright © Asia Pac J Pharmacother Toxicol. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Submit Manuscript

Submit Manuscript